“This boy is a thief, they should just let him die.”

We stopped the car when we suddenly saw a young man laying on his back in the middle of the highway. Thick, dark blood running out of the back of his skull, short jerking breaths, eyes flickering back and forth, body crooked into an unnatural position. The heat was unbearable, the sun was stinging.

There was a pickup truck on the side of the road, the men in the back were discussing, hesitating whether to stay or to leave. “He’s a thief, he jumped out! We are going to the police!” the men shouted as the car drove away.

We were left alone with a body we didn’t know anything about. There was a rope tied around the boy’s wrist, he had been tied up like an animal. He was wearing nothing but a pair of jeans shorts. His lips were dry and he had bad wounds all over his body. He looked younger now when we were closer, like a teenager, alive and awake, but not present. What happened here?

“We have to set up the warning triangles from the cars.” “We have to get the boy out of this sun, he is barely breathing.”

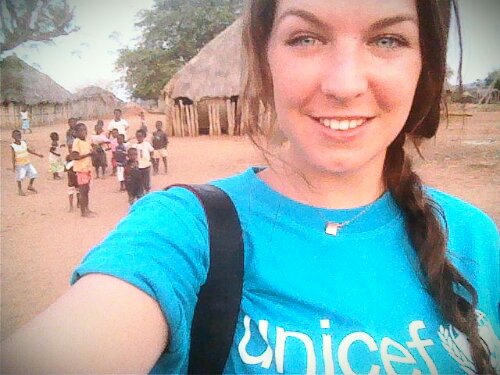

We brought umbrellas for shadow, a first aid kit, desinfection fluids. A person in our group was a doctor, the first thing he did was putting gloves on. “Of course.” I thought, running the HIV prevalence numbers in the province through my head while looking at my legs that were covered by small drops of blood. The boy was coughing and the wind was carrying the blood my way. “You have no open wounds there, Caroline. Focus.” I had bought a simcard from a differnt provider as I knew my normal number wouldn’t work out in the field. It was the only phone with reception and I called the only medical doctor in the entire district, I had saved the number in my phone just in case I would need it. The ambulance would be there in 30 minutes, at least. We were very far out in the middle of nowhere.

Curious people from the villages nearby stopped to have a look. The level of proactivity from their side was below zero. “Get two strong branches, we need to move the body.” We took our mosquito nets and secured them between the branches, building a stretcher. A person walked around desinfecting hands. I finally got that blood off my legs. The boy went into a seizure attack.

“Keep that head up, he is choking on his own tongue!” Basic things you learnt in school come back to you as the most obvious things ever. You forget that it’s not clear to everybody that a wounded person might need help breathing and keeping their airwars cleared. That a body and head that clearly has suffered from an impact shouldn’t be moved around too much. What was clear was that this young man had hit his head very hard against the paved road.

The men lifted the boy using the improvised stretcher and took him to the side of the road, into the shadow. The doctor was keeping the head in place as the boy had a seizure again. “This happens when things are starting to go really bad on the inside.” the doctor quietly explained in English. “I am not very hopeful about this one, this is all taking way too long.” The endless wait for the ambulance.

The people with the pickup truck came back. They told us that the boy had stolen some cows. The men had caught him and his three friends when they were on their way to the city to sell the cows, it was 11 cows. They had tied the boys up and were taking them to the police station when this one suddenly jumped out of the car. A man came, it was the boy’s uncle. “His name is Edmo, he is almost 20 years old.”

“Why don’t they just leave him here to die?” somebody in the group said in a local language. “Yeah, he is just a thief.” a person added. Our driver understood enough. “A judge can tell you if he is a thief, and a prison will punish him if it is true! Who are you to decide if a person is to live or not? You are responsible by leaving him here instead of taking him immediately to the health center – you are the one’s who will be judged for murder.” the men kept quiet. The ambulance wasn’t arriving. We shared the water we had with the villagers.

“This thing won’t open, it’s closed.” a man said, fumbling around clumsily with the lock at the back of the pickup truck. “I guess we have to just throw him in from above or something.” he stopped trying and waited for further instructions. I grabbed the rope holding the door closed and untied it, it was a very simple knot. “What do you mean it doesn’t open?!” I was so angry about the lack of proactivity that I was boiling on the inside. The men lifted the man into the back of the car. He sounded as if he wanted to scream out in pain but didn’t have energy or control enough to do so.

The pickup drove off. A dying boy, ten clueless men and an uncle. 45 minutes after the accident. We urgently needed to leave in the opposite direction.

“Are you sure they are taking him to the health centre now?” I was in doubt. “Yes, they are many and the uncle is there,” the driver answered. “If there were only four of them it could have been dangerous”.

–

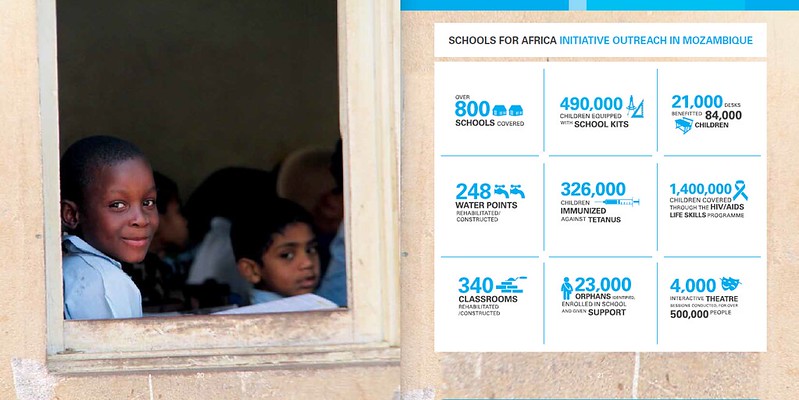

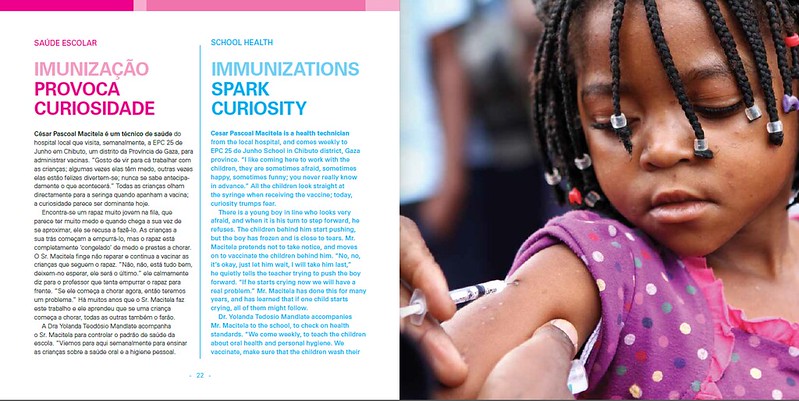

The doctor called us later in the evening. The boy had made it to the health center but needed to be transported to the nearest city 100km away, as the local health centers don’t have enough capacity to take care of such serious cases. He died on the way there. Because he stole a cow. Because people chose not to save him. Because there was no ambulance close enough. Because this is Mozambique, one of the world’s poorest countries.