Author: Caroline Bach

The Kingdom of Magic

Already on our first day, we spoke about there being something mysteriously beautiful about the little kingdom of Swaziland, both it in the smiles of the people and in the breathtaking landscapes. On the second day, when we got to see the animals, there was no doubt about it – Swaziland is a magical place.

We arrived to Swaziland early in the morning and drove straight to Shewula mountain camp which is a community camp located on the top of a mountain, overlooking a valley. We got our huts and sat for a while on the rock before we had lunch and got a tour around the area.

We walked through never ending fields and I kept wondering whether the guide had any idea where he was going. We followed the rhythmic sound of drums until we ended up in a place with six huts and some sort of celebration where every single person except the youngest was as drunk as drunk can get. The people were dancing, falling over each other and laughing. Ladies were jumping around with infants on their backs, little heads wobbling back and forth and toothless men were singing out loud with big cups of homemade beer in their hands. Somebody had some sort of a seizure that looked almost like epilepsy but wasn’t. It was strange. The people were happy to see us and they wanted us to dance, take photos and drink with them. I was entertained by the many smiles but concerned and saddened by the confused children with clear signs of malnutrition and vitamin A deficiency.

As we walked back to the camp I couldn’t stop thinking about how working in the field of development doesn’t allow one to naively enjoy these kinds of “attractions” the way I maybe could before, and how much working for the WFP changed me and my understanding of the importance of proper nutrition. Instead of meeting with a group of drunk and funny people that I could have filmed and uploaded to Youtube to laugh about, I had just had an encounter with living examples of many of Swaziland’s very serious social problems. I was thankful for being able to experience these moments in a different way now than I could before, with a wider understanding of what I am witnessing and of the effects and implications of my acting.

Swaziland sparked a lot of food for thought, I was contemplating the ways in which my travelling had changed the recent years and I spent time writing in my journal while sitting on the edge of the mountain. Around that time, the sun started setting, and except from some buzzing, we all enjoyed the silence, the fresh air and one of the most beautiful and crisp sunsets I have seen.

With the evening came our Swazi dinner. And the ladies who work at the camp had prepared something out of this world. It was as tasty as it was colourful and fresh, the chicken in some sort of peanut butter sauce had just been killed, and there were sausages, something green, something orange, potatoes.. and ah.. I just couldn’t stop eating even when I was completely full. It was without any doubt the best meal I have had in many months.

And as if the day couldn’t have gotten any more special, the black sky started lighting up just when we had finished eating. It was thunder, in the distance, silent and just the way I love it. We took our torches and went out to the rock again, watching and smelling the violent storm as it was approaching. The thunderbolts were striking down all around us and when it came really close we decided that we didn’t want to stand exposed out there, so we hid in a hut together with the ladies that had cooked for us. They were very afraid and they had put the lights out and the gas stoves off, tea was not an option and it was absolutely forbidden to touch milk while the storm was close – because it’s from the cow! I still don’t get that part.

The storm continued for a while and some of us went outside to stand under a small roof and watch it strike and the sky light up in a way that was completely unpredictable and random. The storm passed and we had that cup of tea we had been waiting for, then we ran through the mud and jumped into our huts.

Even sleeping was amazing in Shewula. The silence on the top of the mountain, the fresh air that was coming in through the grass roof and the morning light that woke us up. We started the day looking out over the valley again and I felt very rested and in harmony.

Some of us decided that we wanted to see more of Swaziland so we drove off in our car, playing local radio stations and bumping to African techno and other entertaining music. We were driving on beautiful roads with the Swazi landscapes all around us and people were waving their hands as we were passing, giving us the thumbs up, always smiling. Not sure about where to go we just picked the closest place we could find. We soon realized that we had chosen the best of the parks that Swaziland has to offer, just like that, because it was that kind of weekend.

We ate really tasty food at almost no cost at the Hlane National Park and took a stroll around the area while waiting for our guide. The first animals we met were a big group of rhinos and hippos that approached us and stood just two metres away behind a small electric fence that was separating the restaurant and camp from the rest of the park. I was enchanted. By the way the animals were interacting with each other, by the way there were curious about us and by their rough skin and little black eyes. One of the hippos showed me its tounge for staring too much! haha

It was just the three of us going for a guided tour in a huge jeep and with a guide named Maxwell, so we got to decide what we wanted to see first. The lions! we said, which Maxwell answered would be a difficult task. It proved not to be, because almost just as we had entered the closed lion section, we saw a lion sleeping in the grass. Maxwell drove up very close to it and it didn’t even bother to lift its head. We were watching it and Maxwell was whispering, telling us about the life of lions, about how they hunt and about how they can jump two metres to attack. Just as he said that, the lion suddenly stood up and looked very angry. Maxwell jumped down into his seat, trying to start the car, his whole face melting with fear. I saw the lion coming closer and hid my head between my knees as Maxwell got the jeep started and backed away. I looked up when we were a bit away and saw the lion again. It gave us a big yawn, showing off its fangs, and smiled. Then it roared five times. Two long and three short roars, and Maxwell explained that people used to say means: Who is the king?! Who is the king?! It’s me, it’s me, it’s me.

We drove on and watched a beautiful elephant drink endless amounts of water, a curious giraffe eating and chewing loudly just like a camel, a lot of pretty impala skipping around and some random birds. And a Pumba! Overall, it was clear that the park was the animal’s territory and not the other way around. They were deciding whether we could see them or not and how close we were allowed to approach them. It was a very powerful feeling to stand a bit away from an elephant, knowing that it was aware of your presence and that if you didn’t respect it, it had the power to kill you. Suddenly, just like that, we weren’t the masters of the situation or the top of the food chain and it was as scary as it was beautiful to be inferior to these animals. I asked Maxwell whether he had a weapon in the jeep in case something would happen, he did.

We got back into the car and I got to drive on our way back to Mozambique. Driving on the left side of the road for the first time in my life didn’t feel as weird as I had expected and I was very happy to finally do so. There was a lot to think about after these two days of thought provoking experiences and moments. Thinking about it now, I am convinced that I will be going back, to get more of those smiles, more of the Swazi air, more of the animals, and more of that magic.

Hard skin

I won’t be able to share my impressions from Swaziland with you yet – but I can let you see these two amazing creatures that I met in Hlane National Park. It was a truly mindblowing experience – nothing like anything I have ever experienced before. Animals look and feel completely different when they are not in captivity, when you are on their territory, and when they are the one’s setting the rules.

“We, the Web kids.”

.

Piotr Czerski, a Polish author, has written a brilliant piece on internet censorship entitled “My, dzieci sieci” which translates to “We, the Web kids” and appeared in the Polish newspaper Dziennik Baltycki a month ago. Czerski has managed to explain the importance that the Internet has had to our generation – and the way it now is a perfectly natural part of our lives, affecting the way we search, share, enjoy and think.

We, the Web Kids.

by Piotr Czerski

There is probably no other word that would be as overused in the media discourse as ‘generation’. I once tried to count the ‘generations’ that have been proclaimed in the past ten years, since the well-known article about the so-called ‘Generation Nothing’; I believe there were as many as twelve. They all had one thing in common: they only existed on paper. Reality never provided us with a single tangible, meaningful, unforgettable impulse, the common experience of which would forever distinguish us from the previous generations. We had been looking for it, but instead the groundbreaking change came unnoticed, along with cable TV, mobile phones, and, most of all, Internet access. It is only today that we can fully comprehend how much has changed during the past fifteen years.

We, the Web kids; we, who have grown up with the Internet and on the Internet, are a generation who meet the criteria for the term in a somewhat subversive way. We did not experience an impulse from reality, but rather a metamorphosis of the reality itself. What unites us is not a common, limited cultural context, but the belief that the context is self-defined and an effect of free choice.

Writing this, I am aware that I am abusing the pronoun ‘we’, as our ‘we’ is fluctuating, discontinuous, blurred, according to old categories: temporary. When I say ‘we’, it means ‘many of us’ or ‘some of us’. When I say ‘we are’, it means ‘we often are’. I say ‘we’ only so as to be able to talk about us at all.

1.

We grew up with the Internet and on the Internet. This is what makes us different; this is what makes the crucial, although surprising from your point of view, difference: we do not ‘surf’ and the internet to us is not a ‘place’ or ‘virtual space’. The Internet to us is not something external to reality but a part of it: an invisible yet constantly present layer intertwined with the physical environment. We do not use the Internet, we live on the Internet and along it. If we were to tell our bildnungsroman to you, the analog, we could say there was a natural Internet aspect to every single experience that has shaped us. We made friends and enemies online, we prepared cribs for tests online, we planned parties and studying sessions online, we fell in love and broke up online. The Web to us is not a technology which we had to learn and which we managed to get a grip of. The Web is a process, happening continuously and continuously transforming before our eyes; with us and through us. Technologies appear and then dissolve in the peripheries, websites are built, they bloom and then pass away, but the Web continues, because we are the Web; we, communicating with one another in a way that comes naturally to us, more intense and more efficient than ever before in the history of mankind.Brought up on the Web we think differently. The ability to find information is to us something as basic, as the ability to find a railway station or a post office in an unknown city is to you. When we want to know something – the first symptoms of chickenpox, the reasons behind the sinking of ‘Estonia’, or whether the water bill is not suspiciously high – we take measures with the certainty of a driver in a SatNav-equipped car. We know that we are going to find the information we need in a lot of places, we know how to get to those places, we know how to assess their credibility. We have learned to accept that instead of one answer we find many different ones, and out of these we can abstract the most likely version, disregarding the ones which do not seem credible. We select, we filter, we remember, and we are ready to swap the learned information for a new, better one, when it comes along.

To us, the Web is a sort of shared external memory. We do not have to remember unnecessary details: dates, sums, formulas, clauses, street names, detailed definitions. It is enough for us to have an abstract, the essence that is needed to process the information and relate it to others. Should we need the details, we can look them up within seconds. Similarly, we do not have to be experts in everything, because we know where to find people who specialise in what we ourselves do not know, and whom we can trust. People who will share their expertise with us not for profit, but because of our shared belief that information exists in motion, that it wants to be free, that we all benefit from the exchange of information. Every day: studying, working, solving everyday issues, pursuing interests. We know how to compete and we like to do it, but our competition, our desire to be different, is built on knowledge, on the ability to interpret and process information, and not on monopolising it.

2.

Participating in cultural life is not something out of ordinary to us: global culture is the fundamental building block of our identity, more important for defining ourselves than traditions, historical narratives, social status, ancestry, or even the language that we use. From the ocean of cultural events we pick the ones that suit us the most; we interact with them, we review them, we save our reviews on websites created for that purpose, which also give us suggestions of other albums, films or games that we might like. Some films, series or videos we watch together with colleagues or with friends from around the world; our appreciation of some is only shared by a small group of people that perhaps we will never meet face to face. This is why we feel that culture is becoming simultaneously global and individual. This is why we need free access to it.This does not mean that we demand that all products of culture be available to us without charge, although when we create something, we usually just give it back for circulation. We understand that, despite the increasing accessibility of technologies which make the quality of movie or sound files so far reserved for professionals available to everyone, creativity requires effort and investment. We are prepared to pay, but the giant commission that distributors ask for seems to us to be obviously overestimated. Why should we pay for the distribution of information that can be easily and perfectly copied without any loss of the original quality? If we are only getting the information alone, we want the price to be proportional to it. We are willing to pay more, but then we expect to receive some added value: an interesting packaging, a gadget, a higher quality, the option of watching here and now, without waiting for the file to download. We are capable of showing appreciation and we do want to reward the artist (since money stopped being paper notes and became a string of numbers on the screen, paying has become a somewhat symbolic act of exchange that is supposed to benefit both parties), but the sales goals of corporations are of no interest to us whatsoever. It is not our fault that their business has ceased to make sense in its traditional form, and that instead of accepting the challenge and trying to reach us with something more than we can get for free they have decided to defend their obsolete ways.

One more thing: we do not want to pay for our memories. The films that remind us of our childhood, the music that accompanied us ten years ago: in the external memory network these are simply memories. Remembering them, exchanging them, and developing them is to us something as natural as the memory of ‘Casablanca’ is to you. We find online the films that we watched as children and we show them to our children, just as you told us the story about the Little Red Riding Hood or Goldilocks. Can you imagine that someone could accuse you of breaking the law in this way? We cannot, either.

3.

We are used to our bills being paid automatically, as long as our account balance allows for it; we know that starting a bank account or changing the mobile network is just the question of filling in a single form online and signing an agreement delivered by a courier; that even a trip to the other side of Europe with a short sightseeing of another city on the way can be organised in two hours. Consequently, being the users of the state, we are increasingly annoyed by its archaic interface. We do not understand why tax act takes several forms to complete, the main of which has more than a hundred questions. We do not understand why we are required to formally confirm moving out of one permanent address to move in to another, as if councils could not communicate with each other without our intervention (not to mention that the necessity to have a permanent address is itself absurd enough.)There is not a trace in us of that humble acceptance displayed by our parents, who were convinced that administrative issues were of utmost importance and who considered interaction with the state as something to be celebrated. We do not feel that respect, rooted in the distance between the lonely citizen and the majestic heights where the ruling class reside, barely visible through the clouds. Our view of the social structure is different from yours: society is a network, not a hierarchy. We are used to being able to start a dialogue with anyone, be it a professor or a pop star, and we do not need any special qualifications related to social status. The success of the interaction depends solely on whether the content of our message will be regarded as important and worthy of reply. And if, thanks to cooperation, continuous dispute, defending our arguments against critique, we have a feeling that our opinions on many matters are simply better, why would we not expect a serious dialogue with the government?

We do not feel a religious respect for ‘institutions of democracy’ in their current form, we do not believe in their axiomatic role, as do those who see ‘institutions of democracy’ as a monument for and by themselves. We do not need monuments. We need a system that will live up to our expectations, a system that is transparent and proficient. And we have learned that change is possible: that every uncomfortable system can be replaced and is replaced by a new one, one that is more efficient, better suited to our needs, giving more opportunities.

What we value the most is freedom: freedom of speech, freedom of access to information and to culture. We feel that it is thanks to freedom that the Web is what it is, and that it is our duty to protect that freedom. We owe that to next generations, just as much as we owe to protect the environment.

Perhaps we have not yet given it a name, perhaps we are not yet fully aware of it, but I guess what we want is real, genuine democracy. Democracy that, perhaps, is more than is dreamt of in your journalism.

___

This piece is published under CC-BY-SA 3.0. Originally published on February 11, 2012, in The Baltic Daily, a local Polish newspaper (Dziennik Baltycki). Translated to English by Marta Szreder. Free to reproduce as long as the author is credited.

Link to original article

Link to more language versions

Swazi

Arte na Rua

It’s Friday again. I’m falling in love with this city with all its cultural happenings and the many opportunities for weekend get-aways. We have to go abroad at least every 30 days to get our passports stamped and visa’s renewed, which gives us a great reason to travel a bit further away and explore. This weekend we’re going to the mysterious little Kingdom of Swaziland.

Here are some shots from last weekend and the “Arte na Rua” festival. One of my roomates was part of a contemporary dance performance, and later we saw and met with the super talented Tofo Tofo boys who are big superstars here. They are two Mozambicans got to dance together with Beyonce in one of her videos after she had found them on Youtube. Oh, the glories of the internetz!

A Smoothie Robot For My Moon Mansion

The moon was full over Maputo a couple of days ago. I was watching it from a couch on a balcony on the 16th floor. Head back, facing the sky.

I’ve told you many great things about SoundCloud, but the best thing about it is when you find a tune like this and the artist is sharing it for free download. I instantly grabbed it and unconditionally love it. See for yourself. Here’s Ricky Eat Acid doing A Smoothie Robot for My Moon Mansion and you can download it by clicking that little arrow to the right of the player. But have a listen first and do let me know what you think about it. Now, enjoy.

Ricky Eat Acid – A Smoothie Robot for my Moon Mansion

(2012)

Good night.

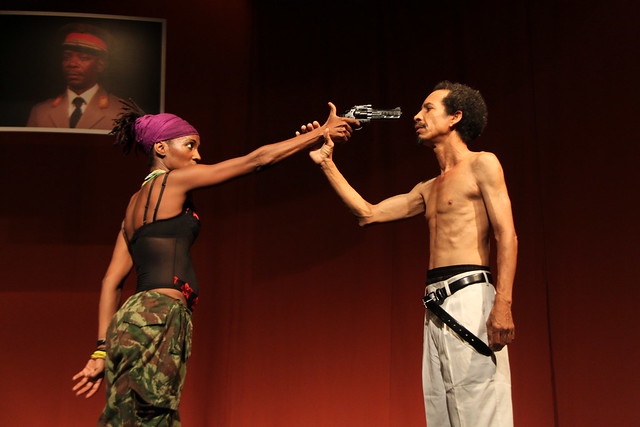

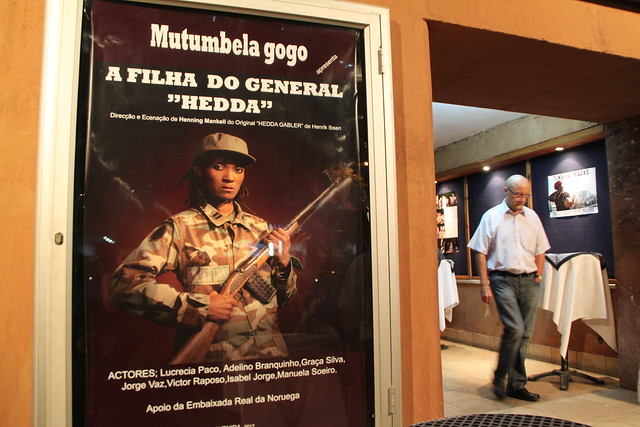

The General’s Daughter

Last friday I went to the premiere of “A filha do General” at Teatro Avenida here in Maputo. The play was a Mozambican interpretation of Henrik Ibsens renowned play Hedda Gabler from 1890. It was performed by the theatre group Mutumbela Gogo and directed by the Swedish writer and director Henning Mankell.

Mankell and the artists have managed to combine a very interesting historical context from Mozambique with Ibsens powerful psychological drama about a dominant yet confused female character sometimes described as the “female Hamlet” – if you are near Maputo and get the opportunity to go, do so.

Silent thunder

The priceless truth

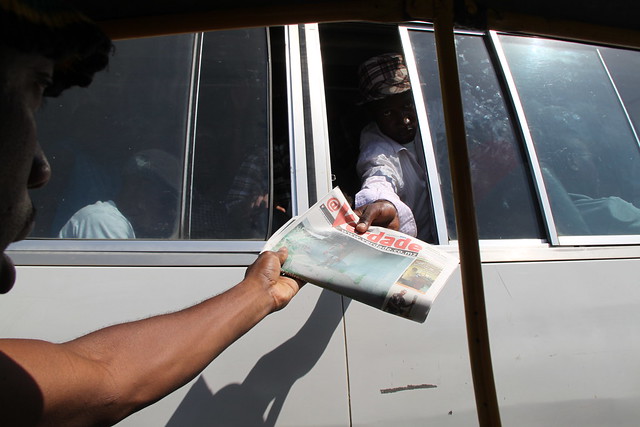

On Saturday I went together with Mozambican @Verdade to the outskirts of Maputo to take part in the distribution of their weekly newspaper. I had been talking to the director of the paper on twitter the day before and he asked me if I would like to come along to see what a distribution looks like, and meet the people who read the paper. So I did.

“A Verdade não tem preço!” Somebody shouted as we drove by in our little tuk-tuk.

“The truth has no price” – which is the slogan of the journal, referring both to the truth as such, and to the newspaper.

@Verdade means “The truth” and it costs nothing. It is distributed with tuk-tuks that drive around the slums and suburbs of Maputo, delivering the paper to people who reach out to grab a copy. People come running, often whistle a little tune to get your attention, get a copy, look you in the eyes and always say thank you. They want this information and they want you to know that they are appreciating it.

Old men, young women with babies, security guards, women carrying baskets with fruit on their heads, young people reaching out from the windows of cars and buses, anbody can get a copy – except the youngest one’s. It was exciting to see the scope of the kinds of people who wanted their copy of the newspaper, and I couldn’t help but wondering what the literacy rate was in the places we went – it didn’t look very promising. But whatever these people’s ability to read well actually is, @Verdade seems to be the only thing a lot of people get to read at all, and it might be their only soure of outside information.

The newspaper is written in fairly simple portuguese with a loud politically oppositional voice, a lot of participatory journalism and articles often focusing on social issues of high imporance to the development of Mozambique. I looked through the issue that we were distributing and it had a big article about how to easily protect babies from malnutrition, which is one of the biggest problems here in Mozambique. So I wouldn’t say the literacy rate is a big obstacle, because if only one person can read and tell the other’s what it’s all about, or if the schooled children get to read for their parents in the evening – it’s still great. And people who can’t read well get to really try and practice. Maybe learn.

Launched in 2008, the newspaper has a distribution of 50,000 per issue and is the most read weekly journal in Mozambique. It was very touching to see how much people actually wanted to read the news. They knew we were coming, they knew who we were, and when we were going back through an area we had already been to, you could see everybody with their heads down, reading. Or maybe at least looking at the pictures.